History and Values

Picasso and the challenge posed by ceramics, on show at the MIC | by Simona Malagoli

One of the greatest artistic geniuses of all time, Pablo Picasso is recognised worldwide for his canvases, for his Cubist paintings and sculpture; unfortunately, far fewer people are aware of the significant amount of ceramic works he produced, and many of those who are consider them of secondary importance. Throughout his career, Picasso produced over 3000 ceramic works, all of them one-off pieces; he approached this enormous effort as a ceaseless challenge aimed at subverting the existing system of the Fine Arts. The creative process he followed mirrored that of his sculptures and paintings: this clearly shows that Picasso saw ceramics not as a sub-product of his artistic activity, but indeed a means through which he was able to express his creativity in every aspect, and that these works are essential to understanding his art as a whole.

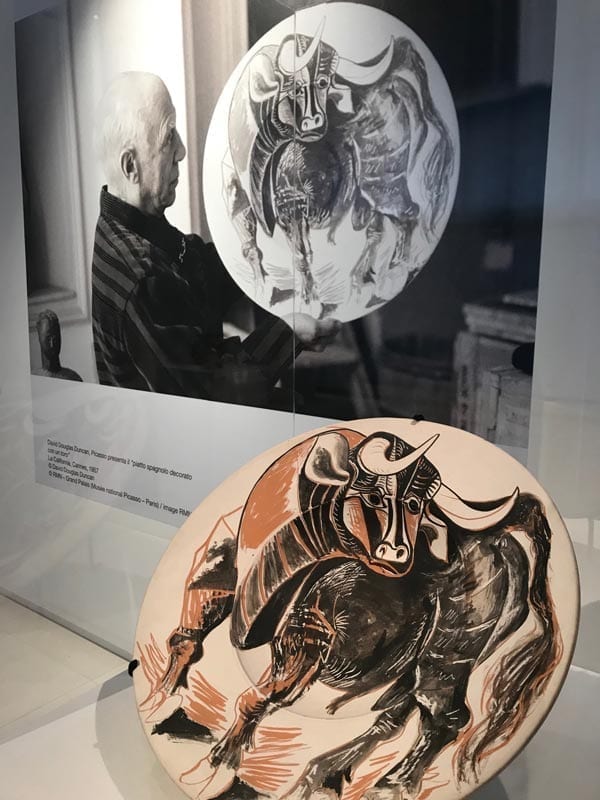

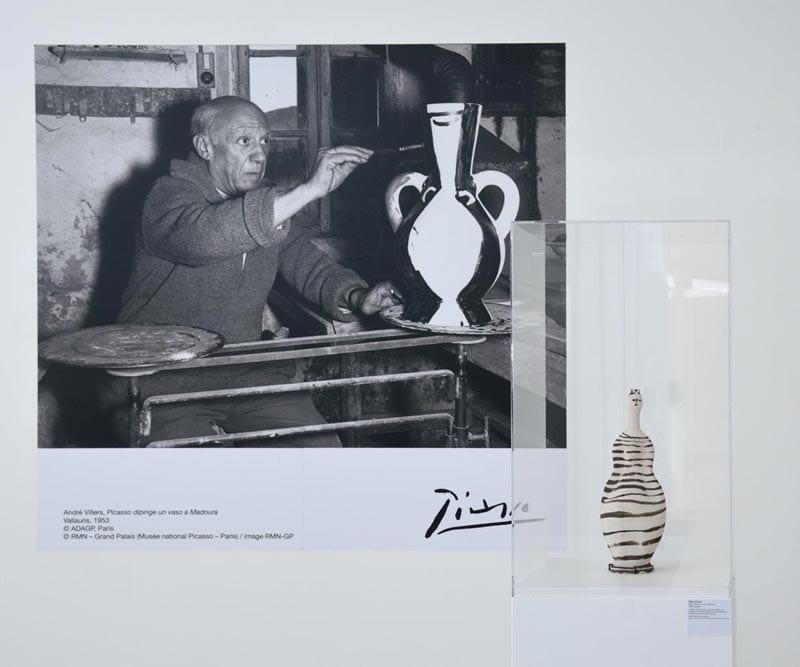

With a view to specifically highlighting how Picasso approached this material – which was the result of much reflection and groundwork rather than a spontaneous impulse – the International Museum of Ceramics (MIC) in Faenza, on 1 November last year, inaugurated the exhibition Picasso. The Challenge of Ceramics, curated by Harald Theil and Salvador Haro González, with the collaboration of Claudia Casali, Director of the MIC. Thanks to an exceptional loan of 50 unique pieces from the collections of the Musée National Picasso in Paris – which organised the international project «Picasso-Méditerranée», of which the MIC event forms part – the exhibition offers an overview of the series-variation-metamorphosis method, which we can already infer from the artist’s preparatory drawings, placing his ceramics in relation with the sources he was inspired by, starting out precisely from objects featured in the MIC collections. Presented alongside works from the tradition and history of ceramics, the Spanish artist’s works, while clearly revealing their modernity, also show how deeply they are rooted in the ancient tradition of this material: from the Greek vases of the Classical Age, with their red and black figures, to the bucchero ware of the Etruscans, as well as the terracotta objects of the pre-Hispanic cultures to popular ceramics from Spain and France. Picasso was very familiar with the numerous examples from the ancient Mediterranean civilisations on display at the Louvre in Paris, and owned many illustrated works on ancient art, and for the themes featured on most of his ceramic works, he took his inspiration from vessels in the shape of human figures or animals, in particular votive objects or drinking vessels, perfume bottles or Etruscan funeral urns, such as the oenochoes, in the shape of a female head, or the women-shaped vases. Mock “ancient” ceramics were even created by the artist, by painting in a similar way on fragments of ceramic exhibits. Picasso was able to take on board all the particular technical characteristics intrinsic to the medium, and created his works in many different ways, orienting his creations towards new horizons every time, yet always consistent with his very own approach to art.

With a view to specifically highlighting how Picasso approached this material – which was the result of much reflection and groundwork rather than a spontaneous impulse – the International Museum of Ceramics (MIC) in Faenza, on 1 November last year, inaugurated the exhibition Picasso. The Challenge of Ceramics, curated by Harald Theil and Salvador Haro González, with the collaboration of Claudia Casali, Director of the MIC. Thanks to an exceptional loan of 50 unique pieces from the collections of the Musée National Picasso in Paris – which organised the international project «Picasso-Méditerranée», of which the MIC event forms part – the exhibition offers an overview of the series-variation-metamorphosis method, which we can already infer from the artist’s preparatory drawings, placing his ceramics in relation with the sources he was inspired by, starting out precisely from objects featured in the MIC collections. Presented alongside works from the tradition and history of ceramics, the Spanish artist’s works, while clearly revealing their modernity, also show how deeply they are rooted in the ancient tradition of this material: from the Greek vases of the Classical Age, with their red and black figures, to the bucchero ware of the Etruscans, as well as the terracotta objects of the pre-Hispanic cultures to popular ceramics from Spain and France. Picasso was very familiar with the numerous examples from the ancient Mediterranean civilisations on display at the Louvre in Paris, and owned many illustrated works on ancient art, and for the themes featured on most of his ceramic works, he took his inspiration from vessels in the shape of human figures or animals, in particular votive objects or drinking vessels, perfume bottles or Etruscan funeral urns, such as the oenochoes, in the shape of a female head, or the women-shaped vases. Mock “ancient” ceramics were even created by the artist, by painting in a similar way on fragments of ceramic exhibits. Picasso was able to take on board all the particular technical characteristics intrinsic to the medium, and created his works in many different ways, orienting his creations towards new horizons every time, yet always consistent with his very own approach to art.

He used mainly existing objects from the standard production of the Madoura pottery workshop in Vallauris, where he worked for 25 years, from 1946 to 1971, or personal works of the owner Suzanne Ramié (such as plates, jugs and vases), using painting to transform them, yet never forgetting to integrate their original shape into the end result, or the importance of the tradition they were an illustration of in the meaning of his work. Many of Picasso’s ceramic works are a reflection of one of the major themes of his art: the relationship between objects and images, expressed through the integration or transformation of objects into works of art. As it is shown by a number of pieces featured in the exhibition, he took broken bricks, for example, and gave them female faces, applying an extraordinarily creative approach. Picasso did not only modify existing shapes; he also created new ones. Attracted by the tactile opportunities offered by handling the material, he worked on objects fresh from the wheel of the potter Jules Agard, adjusting the shape and transforming the pieces, turning them into female-shaped vases, or doves, as we can see in the historical video by Luciano Emmer of 1954 (Picasso in Vallauris), shown in the exhibition room. Comfortably seated in front of the screen, visitors can watch and listen to Picasso at work, revealing fascinating details of his way of working, with his characteristic sense of humour. Regarding the metamorphosis of clay bottles into doves, it is difficult, for instance, to remain indifferent to the words “to make a dove, we have to start by wringing its neck”.

The ceramic production of the Spanish genius is an integral, indissoluble part of his art, and this is evident in several of his ceramic works, in which many of the resources used were taken not only from tradition, but also from his experience as a painter, engraver and sculptor. Several of the themes present are also represented in his paintings, lithographies and drawings, such as the two plates with merry-go-round scenes, or the slab with the Menina, belonging to the series of 56 paintings featuring the same subject, from 1957. This was a two-way process, with his experience with ceramics also influencing his later works using other artistic media.

Like the genius and innovator he was, Picasso did not simply adopt traditional techniques: he turned habitual practice on its head by using unorthodox methods. What he did not know, he invented, drawing on his knowledge of other artistic disciplines and his sharp intuition. Picasso saw the ceramic medium as a creative challenge, an artistic field waiting to be explored, which led him to numerous discoveries, such as the invention of an original graphic work on ceramics: based on his experience with prints, he devised the concept of original impressions on clay slabs (empreintes originales). Printed works on which to paint several unique variants were soon produced as numbered original editions by Picasso, while “authentic replicas” were authorised reproductions of the artist’s works, some examples of which are featured in the exhibition.

Picasso’s desire was for his art to reach a wider audience, moving it away from the exclusive domain of collectors of his works. His ceramics – and these editions in particular – allowed him to obtain this objective: after all, pottery – with objects that were part of everyday life – was a form of popular art, able to help create a closer relationship with modern art.

A special section of the exhibition is of course dedicated to Picasso’s relationship with Faenza: the city’s International Museum of Ceramics owns several pieces by the artist. Following the massive allied bombings in May 1944, the then director Gaetano Ballardini – who founded the MIC – sent a moving letter to Picasso in Madoura, and urged Tullio Mazzotti in Albisola, Gio Ponti and Suzanne and Georges Ramié to request a number of objects from the great artist for the reconstruction of the modern ceramic art collections that had been destroyed, as well as for an exhibition in Faenza. It was thus that in 1950, Picasso made a specific donation, dedicated to the MIC, of an oval plate featuring the Dove of Peace, a memento against wars of all kind. This was followed, in 1951, by other plates featuring faun heads and vases with an archaic, archaeological appearance, and the large vase The Four Seasons, engraved and painted with a pictorial and morphological representation of four graceful female figures. The exhibition is completed with a rich variety of educational material and photographs, featuring documents, newspaper clippings and photographs from the historical archives of the MIC never shown to the public until now. Particularly impressive are the blow-up images of Picasso that welcome the visitor, almost seeming to highlight the artist’s actual intention to engage more closely with the wider public through his ceramics.

February 2020