Factories and ceramists in Civita Castellana

Motivated by a keen interest in the origins and history of the Civita Castellana ceramic industry, Augusto Ciarrocchi, chairman of Ceramica Flaminia and vice chairman of Confindustria Ceramica, has in recent years devoted himself to a painstaking research project on the subject. His efforts culminated in the publication in May 2023 of a book entitled L’industria della ceramica a Civita Castellana. Fabbriche e ceramisti dal 1792 al 1929 (The Ceramic Industry in Civita Castellana. Factories and Ceramists from 1792 to 1929).

While the initial idea was a collaborative project with art historian Professor Giorgio Felini, the latter’s untimely death made it impossible “to resume a discussion that had begun many years previously”. Nonetheless, the author has sought to honour their shared vision by including Giorgio Felini’s La fabbrica di terraglie (The earthenware factory) as an appendix.

The first part of the book explores the history of companies, production techniques and the evolution of the ceramic industry in Civita Castellana from the late 18th century through to the global economic crisis of 1929. The second part addresses sociocultural aspects, offering a social and professional portrait of the working population and entrepreneurs of the period. By listing ceramists and their families, the book aims to fill a crucial gap in our knowledge and provide a comprehensive picture of the local ceramic history of the period against the backdrop of major national and international historical events.

The author highlights the important role of local raw materials, entrepreneurs and foreign ceramists in the early days of industrial production in Civita Castellana. He discusses the events that led to the decline of some product types and the emergence of others, ultimately paving the way for the success of the present-day ceramic industry in the area.

Ciarrocchi’s research reveals the importance of the discovery of white clay suitable for the manufacture of English-style earthenware products and the significant role this played in the development of local artistic and industrial ceramics.

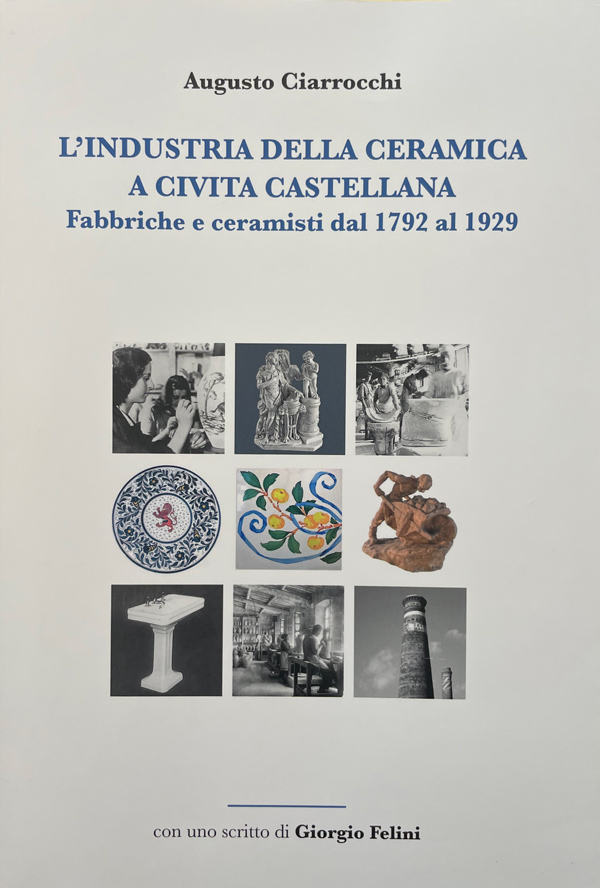

Earthenware production dates back to 1792 when brothers Francesco and Giuseppe Antonino Mizelli together with Giuseppe Valadier secured an exclusive contract signed by Pope Pius VI granting them the right to extract white clay within a 22-kilometer radius of Civita Castellana for a duration of twenty years for the sole production of earthenware. They set up the first pottery in the former Osteria dei Tre Re inn at the Treia bridge, on the left bank of the river that flows below Civita Castellana.

Alongside the production of earthenware, the local presence of white clay or kaolin led to experimentation and short-lived production of small quantities of porcelain. This technically complex production process was carried out in the biscuit style using kaolin from Civita Castellana by Giovanni Volpato and his son Giuseppe in a pottery in Rome.

While the 1840s marked a low point in ceramic production in Civita Castellana, the second half of the 19th century saw a gradual resurgence in terms of both volumes and quality, with new producers emerging on the scene. One of these was the Rovinetti pottery, the only local company considered an industrial-scale enterprise, which exerted a positive influence on local producers from the 1850s onwards. Over the following decades, tableware production grew to become the main source of income for the local population. Together with Tommaso Roversi, Rovinetti introduced modern production techniques borrowed from the Bolognese potteries, especially the use of Vicenza kaolin in place of local white clay for the production of “English-style earthenware”, from at least 1874 onwards.

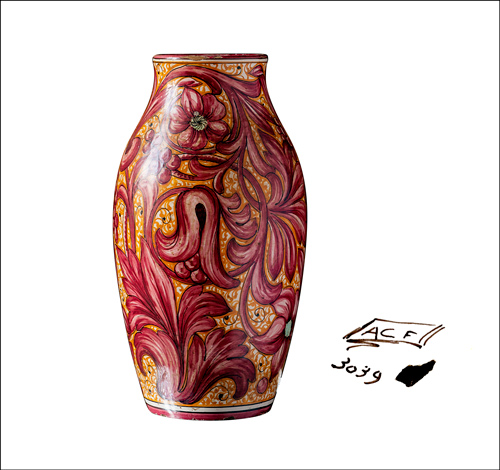

In the second half of the 19th century, the local potteries in Civita Castellana began to shift their attention towards tableware production, which had seen little change since the early 19th century, and began to diversify and cater to a clientele influenced by English and Prussian fashions. In that period, the excessive cost of non-local raw materials and the lack of mechanised production techniques led to the closure of several potteries. In the early twentieth century, the potteries in Civita Castellana began to adopt modern production systems in order to reduce costs and be more competitive against other Italian producers, such as Ginori based in the village of Doccia near Sesto Fiorentino. This ushered in a period of rapid development in ceramic production, encompassing not only traditional fields like tableware and artistic ceramics but also emerging sectors such as sanitaryware and tiles.

Augusto Ciarrocchi reports that the emergence of the first factories producing “odourless English-style toilets” dates back to the early 20th century, as confirmed by Professor De Simone’s technical report on the state of the Civita Castellana factories in 1909. Since articles for personal hygiene and the collection of excrement, particularly earthenware articles and components for latrines, were already being produced in Civita Castellana in the late 19th century, it is plausible that when Italy adopted the odourless water closet systems perfected in England in the 1880s (a system that eliminated unpleasant odours by combining a siphon with a flush), Civita Castellana’s factories were well-equipped to manufacture this new type of ceramic product.

Antonio Coramusi, an artisanal ceramist working at a small majolica workshop in Rome, played a crucial role in the birth of the local sanitaryware industry. He is credited with having studied and developed the new product and conducting the initial tests using local raw materials at Giuseppe Vincenti’s small pottery at the Terrano bridge and then starting up the manufacturing process in his hometown. A publication from 1941 about the history of the Royal Professional School for the Art of Ceramics in Civita Castellana reads: “The sanitaryware industry emerged in Civita Castellana around the turn of the 20th century and, alongside tableware and artistic majolica, made a significant contribution to our city’s development as a nationally important industrial centre.”

The products were soon sold throughout Italy, with Rome being the primary market due to its rapidly expanding population, soon followed by neighbouring regions. However, difficult times were ahead, triggered by the industrial strikes of 1919-1920 and the great economic depression that began in the United States in 1929 and soon spread to Italy.

This is where Augusto Ciarrocchi ends his narrative in order to devote significant space to a list of Civita Castellana ceramists and their families, based primarily on civil registry records from 1871, the year of Civita Castellana’s annexation to the Kingdom of Italy, through to the 1920s. This study provides personal and family records in chronological order, indicating known family relationships and providing information about the profession of ceramist, while also drawing from other sources.

As the author explains, this genealogical work is not intended to be exhaustive as it is based solely on information deriving from registry records, particularly those mentioning professions relating to ceramic production. His aim was to discover more about the Civita Castellana residents who worked in local ceramic production during a specific historical period, “in the hope that this will shed light on a past to which we are deeply indebted”.

November 2023